Interpreting the engravings in Polanski's "Ninth Gate"

In the film “The Ninth Gate,” directed by Roman Polanski, the protagonist gets the assignment, for pay by a wealthy collector, of acquiring the two other copies of a rare seventeenth century book on sorcery, or if not possible, at least reporting what differences there may be among the three extant copies. The collector hopes in that way to use the books in order to get vast power by occult means. The protagonist does indeed find differences, subtle variations among the books' illustrations. In two copies of each of eight of the images, the engravings are the same; but in the third, there are subtle variations. Also, at the bottom of the images that are different appear the initials “LF,” as opposed to the book’s author’s initials on the other two. The ones with "LF" are in a third of each copy's illustrations.

What is to be made of these differences, and what interpretation of the engravings leads one along the true path?

In the film, the collector himself offers an interpretation for the images, and for the initials “LF.” But nothing happens when he puts his ideas into practice. In the novel on which the film is based, a rival collector interprets the images in a different way, based on the cryptic letters at the bottom of each one. But she has not been able to perform any magic with this knowledge. The protagonist himself makes no interpretations and yet seems to be the one who actually succeeds in the end. It is left to the viewer to decide what happened. That, at least, is what I am going to try to do here. But first we need to look at the interpretations that are given by the characters, in the film and in the novel.

A. In the film, by Balkan.

The interpretation of the initials “LF” comes early on. According to the wealthy collector, Balkan, they stand for Lucifer, the real author of the books. They signify that only the engravings with these initials are genuine.

Balkan gives us his interpretation of the individual images near the end of the film, after he has arranged the “genuine” engravings in a particular order. Then he performs a ritual and sets himself on fire, acts which he believes will enable him to become empowered by the Devil. All that happens is that he burns himself to death, screaming in relentless pain.

His interpretation is in the form of a long sentence, in which each phrase corresponds to a specific image. As I quote the sentence, I give the number for the corresponding engraving. Above the sentence are the first three of the engravings,in the order Balkan in the movie rearranges them. Below the sentence are the second three, and below them the last three. I have taken these images from the novel on which the book is based, The Club Dumas, by Arturo Perez-Reverte (pp. 74-82). Be sure to click on each set of images so as to make them large enough to see clearly, and then return to the essay using your back browser (the back arrow at the top left of the screen).

“To travel in silence (1) by a long and circuitous route (4), to brave the arrows of misfortune (3) and fear neither noose nor fire (6), to play the greatest of all games and win (7), foregoing no expense (5), is to mock the vicissitudes of fate (8) and to gain the keys that will unlock (2) the ninth gate (9).”

Then there is the title page, which goes before all the numbered engravings:

The title, translated in the book as "The Nine Doors of the Kingdom of Shadows," in the movie is of course "The Nine Gates" etc. The difference is unimportant. Below the title is "Thus shines the light," and then "Printed in Venice, at the establishment of Aristide Torchia." The date is 1666, and at the bottom "By authority and permission of the superiors."

The nine engravings in the film are a little different from those in the book, in one way. The faces of the people in the engravings physically resemble the characters who appear in the film around the same time we see the engravings. In that same vein, in image 8, instead of a sword, there is a club, wielded by a man who looks like Balkan. The effect is often rather humorous, even when Corso gets hit over the head. For the ninth image, Balkan has identified the castle in the background as a particular one he has purchased. In the film, a photo of it appears on a postcard and also on the wall of his officie suite in New York City. Since it is on fire, he sets the castle on fire after his ritual, as its completion. In the process he also sets fire to himself, although that part is not on the card.

Balkan sees the sentence as applying to himself: he has traveled in silence by a long and circuitous route, sparing no expense, etc. He overlooks the possibility that it might apply to Corso, who does the actual legwork for Balkan. In the film, the faces in the drawings resemble those of the people that Corso meets, and the scenes correspond to what Corso experiences. One face even looks like Corso himself, or rather the actor Johnny Depp, who plays Corso.

The different “gates” then seem to be different tests that allow one entrance to something, if one able to manage a long and circuitous route, brave the arrows of misfortune, etc. It is Corso who does all these things. Yet it is none too clear from Balkan's interpretations what one is entering into. It is simply “the ninth gate,” the gate to a burning castle. Balkan assumes that he is being admitted to a pact with the devil, one that gives him supernatural powers, but there is nothing in his interpretation of the drawings that implies this, apart from the letters LF. It is only legend that associates Lucifer to pacts with the devil giving vast power. In Latin the word “Lucifer” means “light bearer.” The film, at the end, suggests that the successful initiate enters a world of light, corresponding to the meaning of the word. Perhaps “light” is a metaphor for hidden knowledge that the various trials enable an initiate to have. Whether this knowledge implies any power on the earthly plane is unclear.

B. In the novel, by the Baroness.

The owner of one of the copies of the book is the Baroness. In the novel, she tells the protagonist her own interpretations, using the Latin letters on the bottom of each engraving. She says that these are abbreviations of Latin mottoes. In order, this is what she offers for each one. I have slightly condensed her words but not the content.

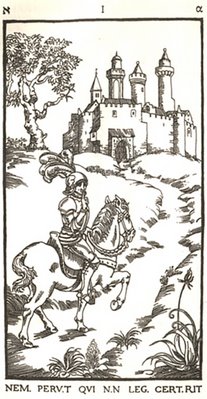

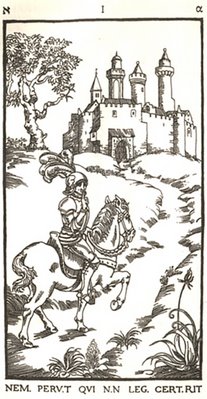

(1) Only he who has fought according to the rules will succeed. (Nemo pervenit qui non legitime certaverit.) "..he [the horseman] is turned to any follower, with a finger to his lip, advising silence...In the background, the city walls surround the secret."

(2) They [the keys] open that which is closed. (Clausae patent.) "The hermit symbolizes knowledge, study, wisdom...And look, at his side there's the same black dog that, according to legend, accompanied Agrippa. The faithful dog. From Plutarch to Bram Stoker and his Dracula, not forgetting Goethe's Faust, the black dog is the animal the devil most often chooses to embody. As for the lantern, it belongs to the philosopher Diogenes who so despised worldly powers. All he requested of powerful Alexander was that he should not overshadow him, that he move because he was standing in front of the sun, the light." Corso asks about the letter Teth. "I'm not sure," the Baroness replies. "The Hermit in the tarot, very similar to this one, is sometimes accompanied by a serpent, or by the stick that symbolizes it. In occult philosophy, the serpent and the dragon are the guardians of the wonderful enclosure, garden, or fleece, and they sleep with their eyes open." [As the film points out somewhere, Teth is the ninth letter of the Hebrew alphabet.]

(3) The lost word keeps the secret. (Verbum dimissum custodiat arcanum.) "A bridge, the union between the light and the dark banks...it links earth with heaven or hell... The bow is the weapon of Apollo and Diana, the light of the supreme power. The wrath of the god, or God. It's the enemy lying in wait for anyone crossing the bridge."

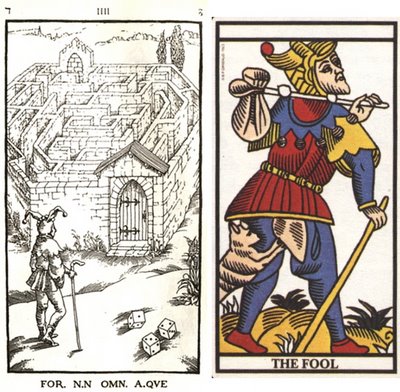

(4) Fate is not the same for all. (Fortuna non omnibus aeque.) "The madman in tarot, God's madman in Islam. And, of course, he's also holding a stick or symbolic serpent. He's the medieval fool, the joker in a pack of cards, the jester. He symbolizes destiny, chance, the end of everything, the expected or unexpected conclusion. In the Middle Ages, the jokers were privileged beings, whose purpose was to remind their masters that they were mortal, that their end is as inevitable as other men's." Corso objects that he is stating the opposite, fate is not the same for all. The Baroness replies, "Of course. He who rebels, exercises his freedom, and takes the risk can earn a different fate. That's what this book is about, hence the joker, paradigm of freedom. The only free man, and also the most wise. The joker is identified with the mercury of the alchemists, Emissary of the gods, he guides souls through the kingdom of shadows..."

(5) In vain. (Frustra.) "The miser is counting his gold pieces, unaware of Death, who holds two clear symbols: an hourglass and a pitchfork. But why a pitchfork and not a scythe? Corso asks. The Baroness replies "Death reaps, but the devil harvests."

(6) I am enriched by death. (Ditesco moro.) "A sentence the devil can utter with his head held high." Corso asks about the hanged man. "Firstly, arcanum twelve in the tarot. But there are other possible interpretations. I believe it symbolizes change through sacrifice. Are you familiar with the saga of Odin? 'Wounded, I hung from a scaffold/swept by the winds/for nine long nights... You can make the following associations. Lucifer, champion of freedom, suffers from love of mankind. He provides mankind with knowledge through sacrifice, thus damning himself."

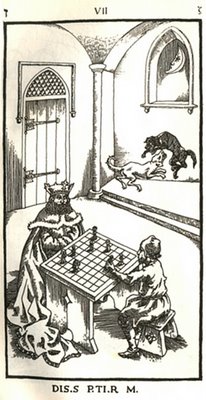

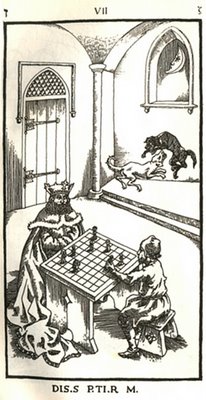

(7) The disciple surpasses the master. (Discipulus potior magistro.) "The king and the beggar play chess on a strange board where all the squares are the same color, while the black dog and the white dog, Good and Evil, viciously tear each other to pieces. The moon, representing both darkness and the mother, can be seen through the window...When we die, we return to her, the darkness from which we came. That darkness is ambiguous, as it is both protective and threatening. The dog and the moon can also be interpreted another way. The goddess of the hunt, Artemis, the Roman Diana, was known to take revenge on those who fell in love with her or tried to take advantage of her femininity. I assume you know the story." Corso says, "Yes. She would let her dogs loose on such men after turning them into stags. So they'd be torn to pieces."

(8) Virtue lies defeated. (Victa iacit virtus.) "The damsel...represents virtue. Meanwhile the wheel of fortune or fate turns inexorably in the background, moving slowly but always making a complete turn. The three figures on it symbolize the three stages which, in the Middle Ages, were referred to as regno (I reign), regnavi (I reigned), and regnabo (I will reign)."

(9). Now I know that from darkness comes light. (Nunc scio tenebris lux.) "What we have here is in fact a scene from Saint John's Apocalypse. The final seal has been broken, the secret city is in flames. The time of the Whore of Babylon has come, and having pronounced the terrible name or the number of the Beast, she rides, triumphant on the dragon with seven heads."

The key to understanding the Baroness’s interpretations as a comprehensive whole, I think, is what she says about the sixth engraving. Lucifer, the alleged author and artist, is the “champion of freedom” who “suffers from love of mankind. He provides mankind knowledge through sacrifice, thus damning himself.” To understand this, we need to realize that the name “Lucifer” in Latin means “light bearer,” and that light is a metaphor for knowledge.

The Baroness could have compared Lucifer not only to Odin but to the Greeks' Prometheus, who defied Zeus by providing humanity with the knowledge of how to make fire--in other words knowledge of how to attain the light. Zeus retaliates against Prometheus by chaining him to a rock and having a vulture eternally gnaw at his liver. If Lucifer is a similar figure, then we are to be grateful to him for leading us out of the darkness. One follows Lucifer when one “rebels, exercises his freedom, and takes the risk” to earn a different fate than that which the king shares with the commoner, i.e. death. In other words, the reward is immortality.

In both film and novel, there is another character who plays a key role, a girl with mysterious powers who helps Corso. In the film it is presumed that she is an agent of Lucifer. Yet she does not act very devilishly. In the novel, she actually says she is with Lucifer, yet she describes a Promethean Lucifer rather than the champion of evil. She tells Corso that aeons ago she was a member of one of Lucifer's legions of angels that followed him in rebelling against God. Now she stands poor and alone. Lying beside her at night, the book explains, Corso had “heard her moan quietly, like a frightened child or like a lonely fallen angel in search of warmth. He'd watched her sleep with her fists clenched, tormented by nightmares of gleaming, blond archangels, implacable in their armor, as dogmatic as the God who made them march in time” (Perez-Reverte, p. 341).

Later she herself explains her past history: “It was very hard. I fought for a hundred days and a hundred nights without hope or refuge. That's the only thing I'm proud of--having fought to the end. I retreated but didn't turn my back, surrounded by others also fallen from on high. I was hoarse with shouting out my fury, my fear and exhaustion. After the battle, I walked across a plain as desolate and lonely as eternity is cold...I still sometimes come across a trace of the battle, or an old comrade who passes by, without daring to look up” (p. 343).

And what is Corso to her? She simply chose him, with that free will that humans take for granted. “Haven't you heard of free will?” she asks. “Some of us have paid a very high price for it” (Perez-Reverte, p. 340). Lucifer and the rebel angels are the champions of the exercise of free will, as opposed to God's angels who unquestioningly follow a Hitler-like dictator, who crushes all who defy him. Corso wants to know “Why me, then? Why didn't you look for someone on the side of the winners?” Her answer: “Because lucidity never wins. And seducing an idiot has never been worth the trouble” (p. 343). At the end of the novel the two of them, Corso and the girl, simply go off together, as lovers and kindred spirits who prefer mystery to clarity and isolation to conformity. “All I could do was go with you,” the girl tells Corso. But “Everyone has to walk certain paths alone” (p. 340).

Over the course of this path, he has gradually taken more initiative and acted more boldly. He has gained the knowledge of himself as a rebel angel--whether as a new recruit or as an old soldier is not important. Is she then the Whore of Babylon of the 9th card, riding triumphant over her newly tamed seven-headed steed?. In the film, the implication is clear; the faces are even similar. In the book it doesn’t seem that way. She is consistently a guardian angel. Perhaps Polanski did not want her to appear too good. The actress, after all, is Polanski’s wife, and he can still remember what happened when he portrayed an earlier wife of his as sweetness and light, in the movie "Fearless Vampire Killers"-—Charles Manson killed her.

C. The images in relation to the medieval Cathars and their Gnostic predecessors.

In the DVD version of the film, Polanski has a voice-over commentary the viewer can listen to. He says something interesting about the castle where everything takes place at the end, and which Corso must go far to find. Polanski says he had in mind the ruined castles in southern France identified with the medieval Cathars, the fortresses they used to protect themselves from the wrath of the Catholic Church’s crusading legions in the 12th and 13th centuries. The peasants called their priests the “good people,” as opposed to the men of the Church, whom the Cathars believed were followers of the false or unjust creator-god. They took the story of God and Satan and turned it on its head. The creator of this world was evil, and those who worshipped the creator-god, whether they knew it or not, were following the devil. The true God was above the false one and welcomed into his eternal realm (as opposed to the false Paradise, which would last only until the end of the universe) those who were able to renounce the creation and its works. By renouncing the creation they had in mind especially the Church’s accumulation of wealth by enforced "tithes," allowing its officials to live well off others’ labor, build grand edifices, and support luxury-loving rulers who did the Church’s dirty work.

The so-called “Cathar prayer,” one of a very few documents preserved from the Cathars, describes Lucifer in ways reminiscent of the Baroness and the Girl in the novel. After a short prayer to the “just God of all good souls” (as opposed to the “alien God” of Genesis and the Catholic Church), the document goes on, in Occitan, the language of that region, to describe the “good souls”:

These are they who come from the Seven Kingdoms, and fell from Paradise where Lucifer lured them hence with the lying assurance that whereas God allowed them the good only, the Devil (being false to the core) would let them enjoy both good and evil...

All those who acknowledged his mastery would descend below and have the power to work both good and evil, as God did in heaven above...(Oldenbourg, p. 376)

This prayer condemns Lucifer for luring good souls out of Heaven to go where they can do evil as well as good. Yet it is they, despite their succumbing to this temptation, who are the good souls. From the perspective of the novel, Lucifer here might be seen as inviting souls out of a place of unfreedom, where only what God already approves can be chosen, into a place where souls experience the agony of freedom and can choose the good only by rejecting evil. In such a place, the evil world created by that God, every soul is in the position of God, who has such power but in heaven did not give it to his angels. By rejecting evil (as Corso has learned to do in the course of the “Nine gates”), a “good soul” has the chance of salvation, the text implies, a restoration to the higher world--a world often portrayed, as in the film, as a place of light. Lucifer remains an ambiguous character in the Cathar Prayer, since he “lures” angels with a “lying assurance.” Yet he is also is a champion of freedom, and those who follow him are the “good souls.” The seven-headed dragon of the ninth image, identified in the film with Corso, could then be a reference to the “seven kingdoms” in heaven from which the “good souls” fell.

From this perspective, the fall of the angels is a heavenly precursor to the fall of Adam and Eve, a good fall of good souls because it leads out of dependence into freedom, a condition of suffering but also of godliness. The snake in the Garden offers Adam and Eve the chance to be “like gods,” by exercising their freedom and gaining, like the Cathar’s “good souls,” the knowledge of good and evil. At the same time, he is leading the first humans into disobedience of God and must thereby be damned for his own sacrifice. Those who follow him, like the “good souls,” give up Eden for a harder life outside of Paradise, yet one lived in freedom.

The Cathars have been linked, both by their enemies at the time and by modern scholars, to the Gnostic Christians of the later Roman Empire. The medieval Catholics called them “Manicheans,” referring to the sect that St. Augustine said he joined before switching to the state-sponsored “Great Church” of the early 5th century. Modern scholars say that the Manicheans are likely one influence out of several for the people who preserved Gnostic traditions into medieval times.

If we go back to the 3rd and 4th century Gnostic texts found in 1945, the so-called “Nag Hammadi Library,” named for the town in Egypt near where they were buried, we find a similar championing of the serpent as against the dictator Jehovah in the Garden of Eden. The following extract is typical, describing the snake with Adam and Eve:

...Then the female spiritual principle came in the snake, the instructor, and it taught them, saying, “What did he say to you? Was it ‘From every tree in the garden shall you eat, yet--from the tree of recognizing good from evil, you shall not eat?’”

The carnal woman said, “Not only did he say ‘Do not eat,’ but even ‘Do not touch it; for the day you eat from it, that day you are going to die.’”

And the snake, the instructor, said, “With death you shall not die, for it was out of jealousy that he said this to you. Rather your eyes shall open and you shall come to be like gods, recognizing evil and good.” And the female instructing principle was taken away from the snake, and she left it behind merely a thing of the earth... (Robinson, pp. 164-165)

Here the “female spiritual principle,” “the instructor,” is meant as a representative of the higher divinity, who visits humanity as a helper, roughly corresponding to the feminine-imaged Sophia, Greek for Wisdom, of the Hebrew Bible, or the Shekhinah of esoteric Judaism. In the Gnostic texts, she works to undermine the rule of the lower god, the dictatorial, insecure world-creator Jehovah, and protect humanity in its quest toward knowledge (in Greek, gnosis) and the world of light. It is she, for example, who warns Noah of God’s wrathful flood. The same occurs in late Jewish scripture, notably Wisdom of Solomon 10:4. The girl in “The Ninth Gate” plays a similar role with Corso. This “female spiritual principle” in other Gnostic texts is identified with a divine emanation named the Lustful Sophia, or perhaps the Desire of Sophia, who like the girl in the novel has been ejected from the divine realm for taking undue initiative, following her desire, in a realm of conformist spirits.

Another point relating to the progress from darkness to light is the title of the book whose contents Corso has been examining, "De Umbrarum Regni Novem Portis," the Nine Doors of the Kingdom of shadows. Here is the title page again.

One might assume, with Balkan, that the "Kingdom of Shadows" is the object of the quest, the world ruled over by the Devil, to which the nine doors admit access. The Baroness refers to the kingdom of shadows that place where Mercury guides souls, in other words the road traveled by the soul on its way to Hades. But in Platonic and Gnostic thought the "place of shadows" was this world of matter and the senses. Plato's "allegory of the cave" in his Republic held that the things of this world are like shadows on a cave wall, cast by cut-out shapes that are themselves copies of true reality outside the cave. In other words, the "kingdom of shadows" is not the object of the quest, but rather that which one must overcome so as to leave it; the "nine doors of the kingdom of shadows" in the title might we on the road traveled after death, but they might also be in this world--leading one out, into the light. "Thus shines the light," says the motto; the way is where the light shines, in a world of darkness, shadows and reflections off the cavern wall. The goal is to enter the light of day.

On the title page, a serpent is wrapped around a tree that is struck by lightning, breaking off one of its branches. The serpent around a tree was, in one Gnostic text, "Hypostasis of the Archons," the incarnation not of the Devil but of the emanation Sophia, Greek for Wisdom, who introduces Eve to knowledge of a realm above this Paradise. The lightning from above would then be that knowledge descending below. The limb breaking off is one more soul recalling its super-celestial destiny, even while losing the Paradise of Jehovah's "thou shalt not."

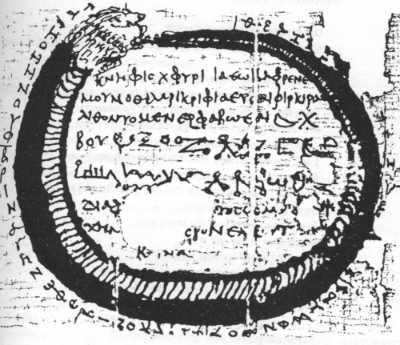

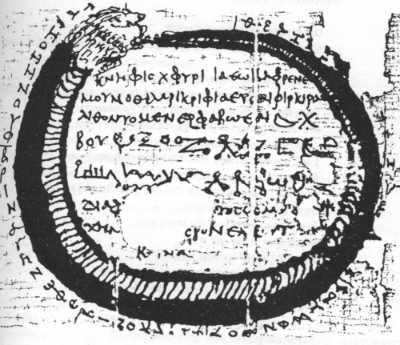

But this serpent, the one on the Tree of Knowledge, was not depicted with its tail in its mouth. That one, the Uroboros, is Sophia's son and enemy Jehovah, who indeed "guards the wonderful enclosure," as the Baroness interprets it--by means of his fearful cherubim. The Uroboros also represented time, always consuming itself in its passage. The true Paradise was beyond time. Some Gnostics described this serpent as encircling the universe, thus effectively keeping souls out of the greater Paradise above him (see below, a modern scholar's reconstruction of the so-called "Ophite diagrams" described in Roman times).

Corresponding to this modern drawing is a 3rd century drawing of the Uroboros on papyrus:

In this context, the limb breaking off from the tree as a result of lightning would be a soul that had reached too far, beyond its designated limit. In the Gnostic myths, such souls, typified by Sophia herself, do fall temporarily, but eventually may rise to a Paradise beyond externally imposed rules.

D. Appendix: historical associations to the engravings

The Baroness points to tarot for image #6, Arcanum 12, the Hanged Man, and for image #2, Arcanum 9, the Hermit (above and below). If we compare the engravings with the corresponding cards in the so-called "Ancient Tarot of Marseille," the similarity is evident. (Here I am using Paul Marteau's popular 1930 version, which took the original designs from 1760 but with different colors. The 1760 version was in turn based on designs dating back to 16th century Northern Italy.)

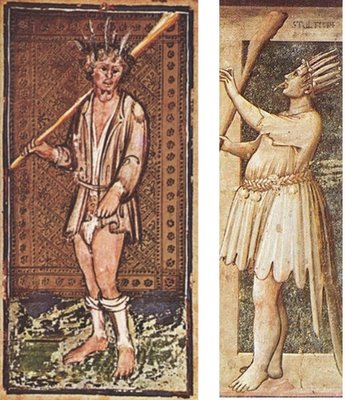

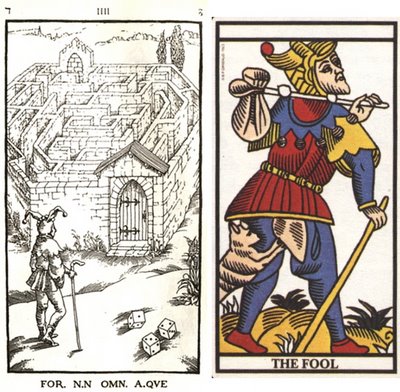

In relation to image #2 she cites the unnumbered arcanum, the Fool or Madman.

There are other associations as well. The two dogs and the moon of #7 relate to the Moon card, Arcanum 18. (HereI am not showing the 1930 Marteau version, which has both dogs the same color, but rather a more historically accurate version from around 1700 by a Parisian engraver named Dodal.)

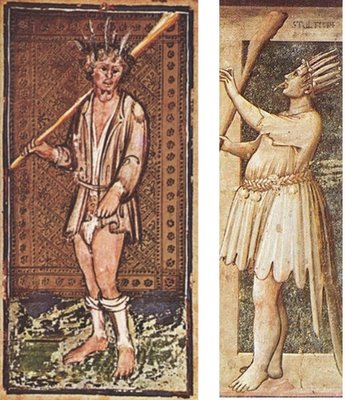

The wheel in the background of #8 is featured in the Wheel of Fortune card, Arcanum 10. The man or angel with the sword or club in #8 appears as a man with a club in early versions of the Strength card, Arcanum 11.

Death, in #5, is Arcanum 13, although the resemblance is not great. (We will see a better fit later on.)

The archer of #3 is like Cupid in the Lovers card, Arcanum 6.

The arrow could also be the lightning bolt striking the Tower, Arcanum 16. The burning castle,engraving #9, also corresponds to that tower, crumbling. There is an even closer resemblance between #9 and a "Destruction of the Temple" card in an old Spanish deck.

The general meaning of most of these cards is reversal of fortune, a turning upside down, things turning into their opposite, for good or for ill, in this world or the next.

One theory about the origin of tarot has the Cathars going underground after their defeat by the Crusaders, at least in Italy, and joining the very institutions created to defeat them, notably the “confraternities” of lay people used by the Church as armed gangs against the Cathars in Italian towns. These same confraternities later would have funded the artists of the Renaissance, who were always looking for mysterious symbols to put in their paintings and perhaps had anti-Church feelings themselves. Some of these artists created the first known tarot cards. It would not be surprising, on this reasoning, if there were hints of the Cathars in tarot.

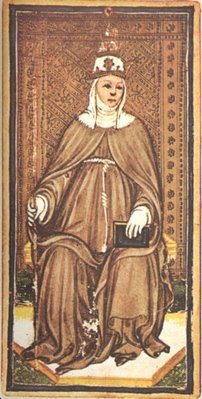

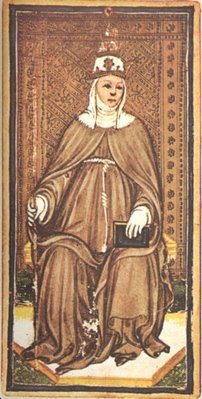

Let me follow up this idea with some supporting examples. In some early tarot decks there was a "Popess" card.

It has been claimed that the clothing worn by the "Popess" here is that of the Gugliamites, a heretical order of mostly women that had a female Pope, chosen to replace the male one in the "third age" about to dawn (Kaplan 1978). She was burned at the stake in 1300. One of the women was related by marriage to an ancestor of the 15th century Duchess of Milan, Bianca Maria Visconti. She or her husband, the Duke of Milan, Francesco Sforza, commissioned the deck of which the image above is one card, the earliest known example of that subject, called "La Papessa".. The Church objected to this subject, because there could be no female pope, even if there was a legendary case if one who had disguised herself as a man.

This particular "Popess" card, it seems to me, bears a resemblance to Giotto's "Justice," a fresco done in Padua only a couple of years after the burning of the heretical "Popess" in nearby Venice. Another possibility, noticed by tarot scholar Gertrude Moakley, is a connection to Giotto's "faith," on account of the similar headpiece. (The tarot headpiece has three rings to just one in "faith." The three-tiered cap corresponds to a famous 1480's representation of legendary sage "Hermes Trismegistes" with such a headpiece.) Here are all three, on the left the Popess card from the Visconti-Szforza tarot, then Giotto's "Justice," and finally his "Faith":

Correspondingly, the "Pope" card, I think, bears a slight resemblance to Giotto's figure of "Injustice":

Similarly, the Visconti-Sforza Fool card may derive from Giotto's "Folly." Giotto in turn got his representation from the "Beggar Pope" of Carnival, a parody of the real Pope.

Several cards in the early decks seem to relate directly to Bianca Maria Visconti and Francisco Sforza, commissioners of the deck. Sforza's father, Muzio "Sforza" Attendola, had broken off his alliance with the Roman Pope in favor of the one in Avignon; the Roman Pope then plastered "hanged man" images of the Duke on Rome's bridges. The "Strength" card has as its title Muzio's nickname, Sforza, which he later adopted as his official last name. An earlier deck, probably the earliest surviving tarot cards there are, was commissioned by her father, then Duke of Milan, Its "Lovers" card, based on the heraldic emblems on the tent, are thought to be Sforza (being given the arms of Pavia, traditionally those of the Duke's heir) and his bride, Bianca Maria Visconti (with the distinctive Visconti "Viper").

Several cards in the early decks seem to relate directly to Bianca Maria Visconti and Francisco Sforza, commissioners of the deck. Sforza's father, Muzio "Sforza" Attendola, had broken off his alliance with the Roman Pope in favor of the one in Avignon; the Roman Pope then plastered "hanged man" images of the Duke on Rome's bridges. The "Strength" card has as its title Muzio's nickname, Sforza, which he later adopted as his official last name. An earlier deck, probably the earliest surviving tarot cards there are, was commissioned by her father, then Duke of Milan, Its "Lovers" card, based on the heraldic emblems on the tent, are thought to be Sforza (being given the arms of Pavia, traditionally those of the Duke's heir) and his bride, Bianca Maria Visconti (with the distinctive Visconti "Viper").

All these cards relate, directly or indirectly, to defiance of papal authority--but ambiguously and deniably, because Sforza did support the Pope who eventually won out during this so-called "Schism" period in the Papacy.

The engravings also bear similarities to alchemical images and Renaissance artworks. The references to keys and locked doors in #1 and #2 is a common one in alchemical texts, dating from about the same time as the tarot images, between the 14th and 17th centuries. For example, a famous book was the “Twelve keys of Basil Valentine.” Alchemy, too, had esoteric spiritual connections. As for the woman riding a seven-headed dragon, the most obvious connection is to engravings by Albrecht Durer (1508) illustrating the Book of Revelation. If you look closely, you will even see a burning castle.

Another 16th century image comes from Alciati's Emblemata:

Alchemy also had its dragons, either biting their tales, as Corso recalls when the Baroness mentions this image, or with three heads, corresponding to salt, sulphur, and mercury. Seven-headed dragons, corresponding to the seven metals and the seven mortal sins, are not unthinkable in this context.

Hieronymus Bosch is another early 16th century artist who drew scenes similar to particular engravings in "The Nine Gates." His "Pedlar" has a similar bridge, with similar symbolism:

He has a similar miser with Death ("Seven Deadly Sins"). In comparison with the tarot card of Death, the fit here is much better.

Likewise, he has mysterious hermits, for example ("St. Anthony"):

and befuddled Fools (his "Ship of Fools"):

Bosch also has plenty of burning castles, for example this one from the "Hell" panel of the "Garden of Earthly Delights":

REFERENCES

Innes, Brian, 1987. The Tarot: How to Use and Interpret the Cards. London: Macdonald & Co.

Dixon, L. (2003). Bosch. New York: Phaedon Press.

Durer, Albrecht, 1990. The Complete Woodcuts (Introduction by Andre Degner, Index by Monika Heffels, Translation by Lilian Stephany). Kirchdorf , Germany: Berghaus Verlag.

Kaplan, Stuart, 1978. History of Tarot, Vol. 1. New York: US Playing Cards.

Oldenbourg, Zoe, 1962. Massacre at Montsegur (tr. by P. Green). New York: Pantheon Books.

Perez-Reverte, Arturo, 1996. The Club Dumas (tr. by S. Soto). New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co.

Robinson, James, Ed., 1988. The Nag Hammadi Library in English, Revised Edition. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

What is to be made of these differences, and what interpretation of the engravings leads one along the true path?

In the film, the collector himself offers an interpretation for the images, and for the initials “LF.” But nothing happens when he puts his ideas into practice. In the novel on which the film is based, a rival collector interprets the images in a different way, based on the cryptic letters at the bottom of each one. But she has not been able to perform any magic with this knowledge. The protagonist himself makes no interpretations and yet seems to be the one who actually succeeds in the end. It is left to the viewer to decide what happened. That, at least, is what I am going to try to do here. But first we need to look at the interpretations that are given by the characters, in the film and in the novel.

A. In the film, by Balkan.

The interpretation of the initials “LF” comes early on. According to the wealthy collector, Balkan, they stand for Lucifer, the real author of the books. They signify that only the engravings with these initials are genuine.

Balkan gives us his interpretation of the individual images near the end of the film, after he has arranged the “genuine” engravings in a particular order. Then he performs a ritual and sets himself on fire, acts which he believes will enable him to become empowered by the Devil. All that happens is that he burns himself to death, screaming in relentless pain.

His interpretation is in the form of a long sentence, in which each phrase corresponds to a specific image. As I quote the sentence, I give the number for the corresponding engraving. Above the sentence are the first three of the engravings,in the order Balkan in the movie rearranges them. Below the sentence are the second three, and below them the last three. I have taken these images from the novel on which the book is based, The Club Dumas, by Arturo Perez-Reverte (pp. 74-82). Be sure to click on each set of images so as to make them large enough to see clearly, and then return to the essay using your back browser (the back arrow at the top left of the screen).

“To travel in silence (1) by a long and circuitous route (4), to brave the arrows of misfortune (3) and fear neither noose nor fire (6), to play the greatest of all games and win (7), foregoing no expense (5), is to mock the vicissitudes of fate (8) and to gain the keys that will unlock (2) the ninth gate (9).”

Then there is the title page, which goes before all the numbered engravings:

The title, translated in the book as "The Nine Doors of the Kingdom of Shadows," in the movie is of course "The Nine Gates" etc. The difference is unimportant. Below the title is "Thus shines the light," and then "Printed in Venice, at the establishment of Aristide Torchia." The date is 1666, and at the bottom "By authority and permission of the superiors."

The nine engravings in the film are a little different from those in the book, in one way. The faces of the people in the engravings physically resemble the characters who appear in the film around the same time we see the engravings. In that same vein, in image 8, instead of a sword, there is a club, wielded by a man who looks like Balkan. The effect is often rather humorous, even when Corso gets hit over the head. For the ninth image, Balkan has identified the castle in the background as a particular one he has purchased. In the film, a photo of it appears on a postcard and also on the wall of his officie suite in New York City. Since it is on fire, he sets the castle on fire after his ritual, as its completion. In the process he also sets fire to himself, although that part is not on the card.

Balkan sees the sentence as applying to himself: he has traveled in silence by a long and circuitous route, sparing no expense, etc. He overlooks the possibility that it might apply to Corso, who does the actual legwork for Balkan. In the film, the faces in the drawings resemble those of the people that Corso meets, and the scenes correspond to what Corso experiences. One face even looks like Corso himself, or rather the actor Johnny Depp, who plays Corso.

The different “gates” then seem to be different tests that allow one entrance to something, if one able to manage a long and circuitous route, brave the arrows of misfortune, etc. It is Corso who does all these things. Yet it is none too clear from Balkan's interpretations what one is entering into. It is simply “the ninth gate,” the gate to a burning castle. Balkan assumes that he is being admitted to a pact with the devil, one that gives him supernatural powers, but there is nothing in his interpretation of the drawings that implies this, apart from the letters LF. It is only legend that associates Lucifer to pacts with the devil giving vast power. In Latin the word “Lucifer” means “light bearer.” The film, at the end, suggests that the successful initiate enters a world of light, corresponding to the meaning of the word. Perhaps “light” is a metaphor for hidden knowledge that the various trials enable an initiate to have. Whether this knowledge implies any power on the earthly plane is unclear.

B. In the novel, by the Baroness.

The owner of one of the copies of the book is the Baroness. In the novel, she tells the protagonist her own interpretations, using the Latin letters on the bottom of each engraving. She says that these are abbreviations of Latin mottoes. In order, this is what she offers for each one. I have slightly condensed her words but not the content.

(1) Only he who has fought according to the rules will succeed. (Nemo pervenit qui non legitime certaverit.) "..he [the horseman] is turned to any follower, with a finger to his lip, advising silence...In the background, the city walls surround the secret."

(2) They [the keys] open that which is closed. (Clausae patent.) "The hermit symbolizes knowledge, study, wisdom...And look, at his side there's the same black dog that, according to legend, accompanied Agrippa. The faithful dog. From Plutarch to Bram Stoker and his Dracula, not forgetting Goethe's Faust, the black dog is the animal the devil most often chooses to embody. As for the lantern, it belongs to the philosopher Diogenes who so despised worldly powers. All he requested of powerful Alexander was that he should not overshadow him, that he move because he was standing in front of the sun, the light." Corso asks about the letter Teth. "I'm not sure," the Baroness replies. "The Hermit in the tarot, very similar to this one, is sometimes accompanied by a serpent, or by the stick that symbolizes it. In occult philosophy, the serpent and the dragon are the guardians of the wonderful enclosure, garden, or fleece, and they sleep with their eyes open." [As the film points out somewhere, Teth is the ninth letter of the Hebrew alphabet.]

(3) The lost word keeps the secret. (Verbum dimissum custodiat arcanum.) "A bridge, the union between the light and the dark banks...it links earth with heaven or hell... The bow is the weapon of Apollo and Diana, the light of the supreme power. The wrath of the god, or God. It's the enemy lying in wait for anyone crossing the bridge."

(4) Fate is not the same for all. (Fortuna non omnibus aeque.) "The madman in tarot, God's madman in Islam. And, of course, he's also holding a stick or symbolic serpent. He's the medieval fool, the joker in a pack of cards, the jester. He symbolizes destiny, chance, the end of everything, the expected or unexpected conclusion. In the Middle Ages, the jokers were privileged beings, whose purpose was to remind their masters that they were mortal, that their end is as inevitable as other men's." Corso objects that he is stating the opposite, fate is not the same for all. The Baroness replies, "Of course. He who rebels, exercises his freedom, and takes the risk can earn a different fate. That's what this book is about, hence the joker, paradigm of freedom. The only free man, and also the most wise. The joker is identified with the mercury of the alchemists, Emissary of the gods, he guides souls through the kingdom of shadows..."

(5) In vain. (Frustra.) "The miser is counting his gold pieces, unaware of Death, who holds two clear symbols: an hourglass and a pitchfork. But why a pitchfork and not a scythe? Corso asks. The Baroness replies "Death reaps, but the devil harvests."

(6) I am enriched by death. (Ditesco moro.) "A sentence the devil can utter with his head held high." Corso asks about the hanged man. "Firstly, arcanum twelve in the tarot. But there are other possible interpretations. I believe it symbolizes change through sacrifice. Are you familiar with the saga of Odin? 'Wounded, I hung from a scaffold/swept by the winds/for nine long nights... You can make the following associations. Lucifer, champion of freedom, suffers from love of mankind. He provides mankind with knowledge through sacrifice, thus damning himself."

(7) The disciple surpasses the master. (Discipulus potior magistro.) "The king and the beggar play chess on a strange board where all the squares are the same color, while the black dog and the white dog, Good and Evil, viciously tear each other to pieces. The moon, representing both darkness and the mother, can be seen through the window...When we die, we return to her, the darkness from which we came. That darkness is ambiguous, as it is both protective and threatening. The dog and the moon can also be interpreted another way. The goddess of the hunt, Artemis, the Roman Diana, was known to take revenge on those who fell in love with her or tried to take advantage of her femininity. I assume you know the story." Corso says, "Yes. She would let her dogs loose on such men after turning them into stags. So they'd be torn to pieces."

(8) Virtue lies defeated. (Victa iacit virtus.) "The damsel...represents virtue. Meanwhile the wheel of fortune or fate turns inexorably in the background, moving slowly but always making a complete turn. The three figures on it symbolize the three stages which, in the Middle Ages, were referred to as regno (I reign), regnavi (I reigned), and regnabo (I will reign)."

(9). Now I know that from darkness comes light. (Nunc scio tenebris lux.) "What we have here is in fact a scene from Saint John's Apocalypse. The final seal has been broken, the secret city is in flames. The time of the Whore of Babylon has come, and having pronounced the terrible name or the number of the Beast, she rides, triumphant on the dragon with seven heads."

The key to understanding the Baroness’s interpretations as a comprehensive whole, I think, is what she says about the sixth engraving. Lucifer, the alleged author and artist, is the “champion of freedom” who “suffers from love of mankind. He provides mankind knowledge through sacrifice, thus damning himself.” To understand this, we need to realize that the name “Lucifer” in Latin means “light bearer,” and that light is a metaphor for knowledge.

The Baroness could have compared Lucifer not only to Odin but to the Greeks' Prometheus, who defied Zeus by providing humanity with the knowledge of how to make fire--in other words knowledge of how to attain the light. Zeus retaliates against Prometheus by chaining him to a rock and having a vulture eternally gnaw at his liver. If Lucifer is a similar figure, then we are to be grateful to him for leading us out of the darkness. One follows Lucifer when one “rebels, exercises his freedom, and takes the risk” to earn a different fate than that which the king shares with the commoner, i.e. death. In other words, the reward is immortality.

In both film and novel, there is another character who plays a key role, a girl with mysterious powers who helps Corso. In the film it is presumed that she is an agent of Lucifer. Yet she does not act very devilishly. In the novel, she actually says she is with Lucifer, yet she describes a Promethean Lucifer rather than the champion of evil. She tells Corso that aeons ago she was a member of one of Lucifer's legions of angels that followed him in rebelling against God. Now she stands poor and alone. Lying beside her at night, the book explains, Corso had “heard her moan quietly, like a frightened child or like a lonely fallen angel in search of warmth. He'd watched her sleep with her fists clenched, tormented by nightmares of gleaming, blond archangels, implacable in their armor, as dogmatic as the God who made them march in time” (Perez-Reverte, p. 341).

Later she herself explains her past history: “It was very hard. I fought for a hundred days and a hundred nights without hope or refuge. That's the only thing I'm proud of--having fought to the end. I retreated but didn't turn my back, surrounded by others also fallen from on high. I was hoarse with shouting out my fury, my fear and exhaustion. After the battle, I walked across a plain as desolate and lonely as eternity is cold...I still sometimes come across a trace of the battle, or an old comrade who passes by, without daring to look up” (p. 343).

And what is Corso to her? She simply chose him, with that free will that humans take for granted. “Haven't you heard of free will?” she asks. “Some of us have paid a very high price for it” (Perez-Reverte, p. 340). Lucifer and the rebel angels are the champions of the exercise of free will, as opposed to God's angels who unquestioningly follow a Hitler-like dictator, who crushes all who defy him. Corso wants to know “Why me, then? Why didn't you look for someone on the side of the winners?” Her answer: “Because lucidity never wins. And seducing an idiot has never been worth the trouble” (p. 343). At the end of the novel the two of them, Corso and the girl, simply go off together, as lovers and kindred spirits who prefer mystery to clarity and isolation to conformity. “All I could do was go with you,” the girl tells Corso. But “Everyone has to walk certain paths alone” (p. 340).

Over the course of this path, he has gradually taken more initiative and acted more boldly. He has gained the knowledge of himself as a rebel angel--whether as a new recruit or as an old soldier is not important. Is she then the Whore of Babylon of the 9th card, riding triumphant over her newly tamed seven-headed steed?. In the film, the implication is clear; the faces are even similar. In the book it doesn’t seem that way. She is consistently a guardian angel. Perhaps Polanski did not want her to appear too good. The actress, after all, is Polanski’s wife, and he can still remember what happened when he portrayed an earlier wife of his as sweetness and light, in the movie "Fearless Vampire Killers"-—Charles Manson killed her.

C. The images in relation to the medieval Cathars and their Gnostic predecessors.

In the DVD version of the film, Polanski has a voice-over commentary the viewer can listen to. He says something interesting about the castle where everything takes place at the end, and which Corso must go far to find. Polanski says he had in mind the ruined castles in southern France identified with the medieval Cathars, the fortresses they used to protect themselves from the wrath of the Catholic Church’s crusading legions in the 12th and 13th centuries. The peasants called their priests the “good people,” as opposed to the men of the Church, whom the Cathars believed were followers of the false or unjust creator-god. They took the story of God and Satan and turned it on its head. The creator of this world was evil, and those who worshipped the creator-god, whether they knew it or not, were following the devil. The true God was above the false one and welcomed into his eternal realm (as opposed to the false Paradise, which would last only until the end of the universe) those who were able to renounce the creation and its works. By renouncing the creation they had in mind especially the Church’s accumulation of wealth by enforced "tithes," allowing its officials to live well off others’ labor, build grand edifices, and support luxury-loving rulers who did the Church’s dirty work.

The so-called “Cathar prayer,” one of a very few documents preserved from the Cathars, describes Lucifer in ways reminiscent of the Baroness and the Girl in the novel. After a short prayer to the “just God of all good souls” (as opposed to the “alien God” of Genesis and the Catholic Church), the document goes on, in Occitan, the language of that region, to describe the “good souls”:

These are they who come from the Seven Kingdoms, and fell from Paradise where Lucifer lured them hence with the lying assurance that whereas God allowed them the good only, the Devil (being false to the core) would let them enjoy both good and evil...

All those who acknowledged his mastery would descend below and have the power to work both good and evil, as God did in heaven above...(Oldenbourg, p. 376)

This prayer condemns Lucifer for luring good souls out of Heaven to go where they can do evil as well as good. Yet it is they, despite their succumbing to this temptation, who are the good souls. From the perspective of the novel, Lucifer here might be seen as inviting souls out of a place of unfreedom, where only what God already approves can be chosen, into a place where souls experience the agony of freedom and can choose the good only by rejecting evil. In such a place, the evil world created by that God, every soul is in the position of God, who has such power but in heaven did not give it to his angels. By rejecting evil (as Corso has learned to do in the course of the “Nine gates”), a “good soul” has the chance of salvation, the text implies, a restoration to the higher world--a world often portrayed, as in the film, as a place of light. Lucifer remains an ambiguous character in the Cathar Prayer, since he “lures” angels with a “lying assurance.” Yet he is also is a champion of freedom, and those who follow him are the “good souls.” The seven-headed dragon of the ninth image, identified in the film with Corso, could then be a reference to the “seven kingdoms” in heaven from which the “good souls” fell.

From this perspective, the fall of the angels is a heavenly precursor to the fall of Adam and Eve, a good fall of good souls because it leads out of dependence into freedom, a condition of suffering but also of godliness. The snake in the Garden offers Adam and Eve the chance to be “like gods,” by exercising their freedom and gaining, like the Cathar’s “good souls,” the knowledge of good and evil. At the same time, he is leading the first humans into disobedience of God and must thereby be damned for his own sacrifice. Those who follow him, like the “good souls,” give up Eden for a harder life outside of Paradise, yet one lived in freedom.

The Cathars have been linked, both by their enemies at the time and by modern scholars, to the Gnostic Christians of the later Roman Empire. The medieval Catholics called them “Manicheans,” referring to the sect that St. Augustine said he joined before switching to the state-sponsored “Great Church” of the early 5th century. Modern scholars say that the Manicheans are likely one influence out of several for the people who preserved Gnostic traditions into medieval times.

If we go back to the 3rd and 4th century Gnostic texts found in 1945, the so-called “Nag Hammadi Library,” named for the town in Egypt near where they were buried, we find a similar championing of the serpent as against the dictator Jehovah in the Garden of Eden. The following extract is typical, describing the snake with Adam and Eve:

...Then the female spiritual principle came in the snake, the instructor, and it taught them, saying, “What did he say to you? Was it ‘From every tree in the garden shall you eat, yet--from the tree of recognizing good from evil, you shall not eat?’”

The carnal woman said, “Not only did he say ‘Do not eat,’ but even ‘Do not touch it; for the day you eat from it, that day you are going to die.’”

And the snake, the instructor, said, “With death you shall not die, for it was out of jealousy that he said this to you. Rather your eyes shall open and you shall come to be like gods, recognizing evil and good.” And the female instructing principle was taken away from the snake, and she left it behind merely a thing of the earth... (Robinson, pp. 164-165)

Here the “female spiritual principle,” “the instructor,” is meant as a representative of the higher divinity, who visits humanity as a helper, roughly corresponding to the feminine-imaged Sophia, Greek for Wisdom, of the Hebrew Bible, or the Shekhinah of esoteric Judaism. In the Gnostic texts, she works to undermine the rule of the lower god, the dictatorial, insecure world-creator Jehovah, and protect humanity in its quest toward knowledge (in Greek, gnosis) and the world of light. It is she, for example, who warns Noah of God’s wrathful flood. The same occurs in late Jewish scripture, notably Wisdom of Solomon 10:4. The girl in “The Ninth Gate” plays a similar role with Corso. This “female spiritual principle” in other Gnostic texts is identified with a divine emanation named the Lustful Sophia, or perhaps the Desire of Sophia, who like the girl in the novel has been ejected from the divine realm for taking undue initiative, following her desire, in a realm of conformist spirits.

Another point relating to the progress from darkness to light is the title of the book whose contents Corso has been examining, "De Umbrarum Regni Novem Portis," the Nine Doors of the Kingdom of shadows. Here is the title page again.

One might assume, with Balkan, that the "Kingdom of Shadows" is the object of the quest, the world ruled over by the Devil, to which the nine doors admit access. The Baroness refers to the kingdom of shadows that place where Mercury guides souls, in other words the road traveled by the soul on its way to Hades. But in Platonic and Gnostic thought the "place of shadows" was this world of matter and the senses. Plato's "allegory of the cave" in his Republic held that the things of this world are like shadows on a cave wall, cast by cut-out shapes that are themselves copies of true reality outside the cave. In other words, the "kingdom of shadows" is not the object of the quest, but rather that which one must overcome so as to leave it; the "nine doors of the kingdom of shadows" in the title might we on the road traveled after death, but they might also be in this world--leading one out, into the light. "Thus shines the light," says the motto; the way is where the light shines, in a world of darkness, shadows and reflections off the cavern wall. The goal is to enter the light of day.

On the title page, a serpent is wrapped around a tree that is struck by lightning, breaking off one of its branches. The serpent around a tree was, in one Gnostic text, "Hypostasis of the Archons," the incarnation not of the Devil but of the emanation Sophia, Greek for Wisdom, who introduces Eve to knowledge of a realm above this Paradise. The lightning from above would then be that knowledge descending below. The limb breaking off is one more soul recalling its super-celestial destiny, even while losing the Paradise of Jehovah's "thou shalt not."

But this serpent, the one on the Tree of Knowledge, was not depicted with its tail in its mouth. That one, the Uroboros, is Sophia's son and enemy Jehovah, who indeed "guards the wonderful enclosure," as the Baroness interprets it--by means of his fearful cherubim. The Uroboros also represented time, always consuming itself in its passage. The true Paradise was beyond time. Some Gnostics described this serpent as encircling the universe, thus effectively keeping souls out of the greater Paradise above him (see below, a modern scholar's reconstruction of the so-called "Ophite diagrams" described in Roman times).

Corresponding to this modern drawing is a 3rd century drawing of the Uroboros on papyrus:

In this context, the limb breaking off from the tree as a result of lightning would be a soul that had reached too far, beyond its designated limit. In the Gnostic myths, such souls, typified by Sophia herself, do fall temporarily, but eventually may rise to a Paradise beyond externally imposed rules.

D. Appendix: historical associations to the engravings

The Baroness points to tarot for image #6, Arcanum 12, the Hanged Man, and for image #2, Arcanum 9, the Hermit (above and below). If we compare the engravings with the corresponding cards in the so-called "Ancient Tarot of Marseille," the similarity is evident. (Here I am using Paul Marteau's popular 1930 version, which took the original designs from 1760 but with different colors. The 1760 version was in turn based on designs dating back to 16th century Northern Italy.)

In relation to image #2 she cites the unnumbered arcanum, the Fool or Madman.

There are other associations as well. The two dogs and the moon of #7 relate to the Moon card, Arcanum 18. (HereI am not showing the 1930 Marteau version, which has both dogs the same color, but rather a more historically accurate version from around 1700 by a Parisian engraver named Dodal.)

The wheel in the background of #8 is featured in the Wheel of Fortune card, Arcanum 10. The man or angel with the sword or club in #8 appears as a man with a club in early versions of the Strength card, Arcanum 11.

Death, in #5, is Arcanum 13, although the resemblance is not great. (We will see a better fit later on.)

The archer of #3 is like Cupid in the Lovers card, Arcanum 6.

The arrow could also be the lightning bolt striking the Tower, Arcanum 16. The burning castle,engraving #9, also corresponds to that tower, crumbling. There is an even closer resemblance between #9 and a "Destruction of the Temple" card in an old Spanish deck.

The general meaning of most of these cards is reversal of fortune, a turning upside down, things turning into their opposite, for good or for ill, in this world or the next.

One theory about the origin of tarot has the Cathars going underground after their defeat by the Crusaders, at least in Italy, and joining the very institutions created to defeat them, notably the “confraternities” of lay people used by the Church as armed gangs against the Cathars in Italian towns. These same confraternities later would have funded the artists of the Renaissance, who were always looking for mysterious symbols to put in their paintings and perhaps had anti-Church feelings themselves. Some of these artists created the first known tarot cards. It would not be surprising, on this reasoning, if there were hints of the Cathars in tarot.

Let me follow up this idea with some supporting examples. In some early tarot decks there was a "Popess" card.

It has been claimed that the clothing worn by the "Popess" here is that of the Gugliamites, a heretical order of mostly women that had a female Pope, chosen to replace the male one in the "third age" about to dawn (Kaplan 1978). She was burned at the stake in 1300. One of the women was related by marriage to an ancestor of the 15th century Duchess of Milan, Bianca Maria Visconti. She or her husband, the Duke of Milan, Francesco Sforza, commissioned the deck of which the image above is one card, the earliest known example of that subject, called "La Papessa".. The Church objected to this subject, because there could be no female pope, even if there was a legendary case if one who had disguised herself as a man.

This particular "Popess" card, it seems to me, bears a resemblance to Giotto's "Justice," a fresco done in Padua only a couple of years after the burning of the heretical "Popess" in nearby Venice. Another possibility, noticed by tarot scholar Gertrude Moakley, is a connection to Giotto's "faith," on account of the similar headpiece. (The tarot headpiece has three rings to just one in "faith." The three-tiered cap corresponds to a famous 1480's representation of legendary sage "Hermes Trismegistes" with such a headpiece.) Here are all three, on the left the Popess card from the Visconti-Szforza tarot, then Giotto's "Justice," and finally his "Faith":

Correspondingly, the "Pope" card, I think, bears a slight resemblance to Giotto's figure of "Injustice":

Similarly, the Visconti-Sforza Fool card may derive from Giotto's "Folly." Giotto in turn got his representation from the "Beggar Pope" of Carnival, a parody of the real Pope.

Several cards in the early decks seem to relate directly to Bianca Maria Visconti and Francisco Sforza, commissioners of the deck. Sforza's father, Muzio "Sforza" Attendola, had broken off his alliance with the Roman Pope in favor of the one in Avignon; the Roman Pope then plastered "hanged man" images of the Duke on Rome's bridges. The "Strength" card has as its title Muzio's nickname, Sforza, which he later adopted as his official last name. An earlier deck, probably the earliest surviving tarot cards there are, was commissioned by her father, then Duke of Milan, Its "Lovers" card, based on the heraldic emblems on the tent, are thought to be Sforza (being given the arms of Pavia, traditionally those of the Duke's heir) and his bride, Bianca Maria Visconti (with the distinctive Visconti "Viper").

Several cards in the early decks seem to relate directly to Bianca Maria Visconti and Francisco Sforza, commissioners of the deck. Sforza's father, Muzio "Sforza" Attendola, had broken off his alliance with the Roman Pope in favor of the one in Avignon; the Roman Pope then plastered "hanged man" images of the Duke on Rome's bridges. The "Strength" card has as its title Muzio's nickname, Sforza, which he later adopted as his official last name. An earlier deck, probably the earliest surviving tarot cards there are, was commissioned by her father, then Duke of Milan, Its "Lovers" card, based on the heraldic emblems on the tent, are thought to be Sforza (being given the arms of Pavia, traditionally those of the Duke's heir) and his bride, Bianca Maria Visconti (with the distinctive Visconti "Viper").All these cards relate, directly or indirectly, to defiance of papal authority--but ambiguously and deniably, because Sforza did support the Pope who eventually won out during this so-called "Schism" period in the Papacy.

The engravings also bear similarities to alchemical images and Renaissance artworks. The references to keys and locked doors in #1 and #2 is a common one in alchemical texts, dating from about the same time as the tarot images, between the 14th and 17th centuries. For example, a famous book was the “Twelve keys of Basil Valentine.” Alchemy, too, had esoteric spiritual connections. As for the woman riding a seven-headed dragon, the most obvious connection is to engravings by Albrecht Durer (1508) illustrating the Book of Revelation. If you look closely, you will even see a burning castle.

Another 16th century image comes from Alciati's Emblemata:

Alchemy also had its dragons, either biting their tales, as Corso recalls when the Baroness mentions this image, or with three heads, corresponding to salt, sulphur, and mercury. Seven-headed dragons, corresponding to the seven metals and the seven mortal sins, are not unthinkable in this context.

Hieronymus Bosch is another early 16th century artist who drew scenes similar to particular engravings in "The Nine Gates." His "Pedlar" has a similar bridge, with similar symbolism:

He has a similar miser with Death ("Seven Deadly Sins"). In comparison with the tarot card of Death, the fit here is much better.

Likewise, he has mysterious hermits, for example ("St. Anthony"):

and befuddled Fools (his "Ship of Fools"):

Bosch also has plenty of burning castles, for example this one from the "Hell" panel of the "Garden of Earthly Delights":

REFERENCES

Innes, Brian, 1987. The Tarot: How to Use and Interpret the Cards. London: Macdonald & Co.

Dixon, L. (2003). Bosch. New York: Phaedon Press.

Durer, Albrecht, 1990. The Complete Woodcuts (Introduction by Andre Degner, Index by Monika Heffels, Translation by Lilian Stephany). Kirchdorf , Germany: Berghaus Verlag.

Kaplan, Stuart, 1978. History of Tarot, Vol. 1. New York: US Playing Cards.

Oldenbourg, Zoe, 1962. Massacre at Montsegur (tr. by P. Green). New York: Pantheon Books.

Perez-Reverte, Arturo, 1996. The Club Dumas (tr. by S. Soto). New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co.

Robinson, James, Ed., 1988. The Nag Hammadi Library in English, Revised Edition. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

8 Comments:

I found this really interesting and well explained. I am a huge fan of the film and as an illustrator I found your links to Bosch very intriguing.

Definitely need to read up on it more, it's fascinating.

Thanks for your scholarly and informative essay. You gave an intriguing comparison of Balkan's arrangement of the nine engravings with other possible interpretations and historical correspondences. We are able to study the fascinating engravings in depth. Altogether this was an illuminating exploration of the book and the film.

I researched this separately on my own but I haven't found an article that explains the engraving as well as you have in this article. Great read. Thanks!

Very fun, many aspects illuminated that I didn't notice on many viewings of the film. Convinces me I must read the book. You might want to note that in the film, the engravings are signed LCF.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Illuminating. This is a great article. I learned loads. So many things that I had missed. Thank you.

Hi Michael.

As a fan of the Nine Gates, I found article absorbing. Subject to your approval, I have linked to it on my FB page here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/3828112347438258/permalink/3911407299108762/

Many thanks for the insight.

Please feel free to visit my FB page at https://www.facebook.com/groups/3828112347438258

Post a Comment

<< Home